Russian folk costume brief description for children. Russian women's folk costume

The traditional costume, widespread over a vast territory of Russia, is quite diverse, especially. Each region had its own characteristic elements in clothing, unique only to that province. The clothes of the elderly woman were different from those of the girl; on weekdays they wore one robe, on holidays they wore completely different outfits.

Peasant clothing

It was possible to distinguish four sets of women's attire: with a paneva, a sundress, an andarak skirt, and a kubelka. Paneva is the oldest element of women's clothing, a set with paneva was formed in the 6th–7th centuries and included a shirt, an apron, a bib, a headdress - a kichka, bast shoes, and was common in many provinces of central Russia and the south of Russia.Shirts, soul warmers, kokoshniks, etc. were worn with sundresses. Women of Altai, the Urals, the Volga region, Siberia, and the north of the European part of Russia dressed up in such clothes. The heyday of this costume occurred in the 15th–17th centuries.

Cossack women of the North Caucasus and the Don wore a dress with a cap, accompanied by a shirt with wide sleeves and long pants. The clothing of men throughout Rus' was monotonous and consisted of a shirt-shirt, narrow pants, bast shoes or leather shoes, and a hat.

Noble costume

The peculiarity of the national Russian dress is the abundance of outerwear, capes and swings. The clothing of the nobility belongs to the Byzantine type. In the 17th century, elements borrowed from the Polish toilet appeared in it. To preserve the originality of the costume, by a royal decree of August 1675, nobles, solicitors, and stewards were forbidden to wear foreign attire.The costume of the nobility was made of expensive fabrics, richly decorated with gold embroidery, pearls, and buttons made of gold and silver. At that time there was no concept - fashion, style did not change for centuries, a rich dress was inherited from generation to generation.

Until the end of the 17th century, national clothes were worn by all classes: boyars, princes, artisans, merchants, peasants. The reformer Tsar Peter I brought the fashion for European costume to Russia and banned the wearing of national vestments for all classes except peasants and monks. The peasants remained faithful to the national decoration until the end of the 19th century.

Nowadays you won’t see a person dressed in a national costume on the street, but some elements inherent in Russian traditional costume have migrated into modern fashion.

Traditional men's and women's clothing were similar; men's and women's suits differed only in details, some elements of cut, and size. The clothes were casual and festive - richly decorated with embroidery, patterned weaving, ornamental compositions made of braid, galloon, sequins and other materials. However, in the Russian village, not all clothes were richly decorated, but only festive and ritual ones. The most beautiful, annual one, was worn only three or four times a year, on special days. They took care of it, tried not to wash it, and passed it on by inheritance.

During the warm period of the year, the main clothing for women and men was a tunic-like shirt. The men's shirt was knee-length or slightly longer, and was worn over the pants, the women's shirt was almost to the toes, and it was sewn in two parts: the lower part was made of coarser fabric, it was called stanina, and the top was made of thinner fabric. A shirt without a collar was usually worn on weekdays, and with a collar on holidays, the collar was low, in the form of a stand, and they called it an ostebka, a slit on the shirt for fastening was made on the side, rarely at the very shoulder, it went vertically down, less often obliquely, from shoulder to the middle of the chest. The shirt was fastened with buttons or tied at the collar with a ribbon; such a shirt was called a kosovorotka.

Women's shirts were usually cut to the floor (according to some authors, this is where the "hem" comes from). They were also necessarily belted, with the lower edge most often ending up in the middle of the calf. Sometimes, while working, shirts were pulled up to the knees. The shirt, which is directly adjacent to the body, was sewn with endless magical precautions, because it was supposed to not only warm, but also ward off the forces of evil, and keep the soul in the body. According to the ancients, it was necessary to “secure” all the necessary openings in finished clothing: collars, hem, sleeves. Embroidery, which contained all kinds of sacred images and magical symbols, served as a talisman here. The pagan meaning of folk embroidery can be very clearly traced from the most ancient examples to completely modern works; it is not without reason that scientists consider embroidery an important source in the study of ancient religion.

Only Russian men wore pants; in the old days, boys did not wear pants until they were 15 years old, and often until their wedding.

Slavic trousers were not made too wide: in surviving images they outline the leg. They were cut from straight panels, and a gusset was inserted between the legs (“in walking”) for ease of walking: if this detail was neglected, one would have to mince rather than walk. The pants were made approximately ankle-length and tucked into onuchi at the shins.

The trousers had no slit, and were held on the hips with the help of a lace - a “gashnik”, which was inserted under the folded and sewn top edge. The ancient Slavs first called the legs themselves, then the skin from the hind legs of the animal, and then the pants, “Gachami” or “Gaschami”. “Gacha” in the sense of “trouser leg” has survived in some places to this day. Now it’s done, the meaning of the modern expression “kept in a cache” is clear, that is, in the most secluded hiding place. Indeed, what was hidden behind the drawstring for the pants was covered not only with outer clothing, but also with a shirt, which was not tucked into the pants. Another name for leg clothing is “trousers”. They were made from canvas or cloth; elegant Russian trousers were made from black plush. In the Kama region, ports were sewn from striped motley fabric.

The national costume of Russian women was the sundress. Until the beginning of the 18th century. Representatives of the upper classes also wore it, and in later times they were preserved mainly only in the rural environment. "Sarafan is a collective term that refers to long, swinging or closed maid's clothing on hangers or sewn-on straps. Presumably the word "sarafan" comes from the Iranian "sarapa" - dressed from head to toe. The first mentions of this type of clothing in Russian sources refer approximately to 1376, where the sarafan is spoken of as a men's shoulder-length, narrow-cut garment with long sleeves."

As a women's (girl's) clothing, the sundress became universally known in Russia starting from the 17th century. Then it was a one-piece, blind dress with sleeves or sleeveless, worn over the head. The sundress with straps became known only after the 17th century. Since the 19th century. and until the 20s of the twentieth century. The sundress served as festive, everyday, work clothes for the peasantry. Festive sundresses were made from more expensive fabrics, while everyday sundresses were made mainly from homespun.

A huge variety of types of sundresses is known, and several varieties could exist simultaneously in each province. All types can be divided into four large groups according to design (cut), starting with the most ancient.

A blind oblique sundress, known in different provinces under the names Sayan, Feryaz, Capercaillie, Sukman, Dubas. Initially, this type of sundress had a tunic-like cut, in which the front and back of the sundress were formed from one piece of fabric, folded in half. A round or rectangular neckline was cut along the fold, sometimes complemented by a small chest slit in the front center. Numerous longitudinal wedges were placed on the sides. Such sundresses were mainly made from homespun fabric - red cloth, homemade black and blue wool - as well as white and blue canvas. Such sundresses were decorated with linings of calico or painted canvas on the neckline, armholes and hem.

Gradually, the tunic-shaped cut practically ceased to be used, and the swinging oblique sundress, made up of three straight panels of fabric - two at the front and one at the back, became very popular. Golovevy sarafan, kitaeshnik, chinese, kletovnik from 4-6 straight panels of checkered homespun, klinnik, krasik, circular, kumashnik. Sundresses of this type were made from a variety of fabrics: home-produced canvas and wool of different colors, calico print, taffeta, damask silk, brocade, nanka, Chinese, and other cotton fabrics. The decorations of such sundresses were also very diverse: lace, red cord, beads, damask, braided, satin stripes located along the lower edge of the hem or along the fastener on the straps.

The most common type, widely used in almost the entire territory of Russian residence, was the round (straight) sundress - satin, asian, dolnik, inflate, rytnik. It was made up of 4-8 straight panels of fabric (mostly factory-made) and was a high, wide skirt, gathered at the chest, with a small fastener in the center in the front or under the left side strap. This sundress had narrow sewn straps. It was very easy to sew, the fabric was light compared to canvas, so it quickly became popular and replaced the slanted sundress. Everyday sundresses of this type were made from checkered homespun motley or factory fabric in dark colors, while festive ones were made from printed material, bright chintz or satin, calico, silk, brocade and other materials. Round sundresses were decorated along the hem and chest with braided stripes, fringe, silk ribbons, braid, and even appliqués.

Less common, which was a unique version of a round sundress, was a sundress with a bodice, consisting of two parts. The first is a fluffy gathered skirt made of several straight panels, the second is a bodice with narrow straps, tightly fitting the chest, it was sewn (partially or completely) to the fluffy skirt.

In addition, in some regions a high skirt (under the chest) without straps was also called a sundress.

Having briefly described the main types of sundresses that existed on the territory of our country by the end of the 19th century, let us consider what existed in the Kama region.

Several varieties of sundress have been noted in the Kama region. The earliest type of sundress should be considered a “blank” sundress, in the early versions - a tunic cut. In the XVIII - XIX centuries. The most common type of sundress was the side-sloping sundress.

In addition to the sundress, in the Kama region almost everywhere the word dubas was used to designate this type of clothing. This term mainly referred to older types of sundresses, most often slanted or made of homespun canvas. “Written documents report that until the 17th century, sundresses and dubass differed only in material; dubassas were made from dyed canvas, and sundresses from purchased fabrics. The festive sundress was trimmed with ribbons and lace and worn with a shirt made of very thin canvas, and those who had the opportunity , - from purchased fabrics. The earliest among the peoples of the Kama region was a blind sundress - dubas. Old dubass were sewn slanted, with a full-length front seam and wide armholes. To this day, dubas has been preserved only by the Old Believers as part of a prayer costume, and they are now sewn from dark satin"

Outerwear

In winter and summer, men and women wore single-breasted caftans; women had a clasp on the right side, and men had a clasp on the left; they were called ponitkas, shaburs, Siberians, Armenians or Azys; despite their typological similarity, they differed in cut details. Ponitki were sewn from homemade cloth - ponitochina, with a straight front and back at the waist, sometimes with gathers or wedges on the sides. A thread covered with canvas or factory fabric was called a gunya, sometimes for greater warmth they were quilted with a tow; gunis were used as festive and everyday clothing. Weekend gunis were covered with painted canvas, and workers, from rough canvas, called sermyaks or shaburs, sewed them from blue canvas for everyday wear and from factory fabrics for holidays. They had a cut-off waist, at first wide pleats - plastic, later fluffy gathers. The front of the shabura was straight, the flaps were fastened with hooks, and it was sewn on a canvas lining, which was sewn only on the chest.

Sheepskin clothing has long been common in the Urals; people wore covered and naked fur coats. Fur coats were covered with canvas, cloth, and rich people covered them with imported expensive material. They were sewn in the old-fashioned way - at the waist and with gathers. Women's fur coats, covered with silk and with collars made of squirrel or sable fur, looked especially elegant.

Travel clothes were sheepskin coats and zipuns. Zipuns were sewn from canvas or gray cloth, they were worn over a thread or a fur coat.

Russian peasants also had clothes specially designed for work and household chores. Men hunters and fishermen wore luzans; Russians borrowed this type of clothing from the Komi-Permyaks and Mansi. A specially woven cross-striped fabric was folded in half and a hole was cut along the fold for the head, the lower ends were secured with ropes at the waist. Canvas was hemmed under the panels at the front and back, and the resulting bags were used to store and carry accessories and loot. For household work in the field and at home, men and women wore blind cuffs of a tunic-like cut with long sleeves over their clothes; the linen of canvas went down to the knees in front, and to the waist in the back.

Belts were an obligatory part of men's and women's costumes; in the northern regions they were also called hemlines or girdles. “Religious beliefs prohibited wearing clothes without a belt, hence the expression “without a cross and a belt,” “unbelted,” meaning that a person’s behavior does not correspond to generally accepted norms of behavior.” Underwear, sundress and outerwear must be belted. Women typically wore a woven or cloth belt, while men wore a leather belt. The woven belts for girdling the shirt were narrow - gazniks, and outer clothing was tied with wide sashes. There were two ways to tie a belt: high under the chest or low under the stomach (“under the belly”). Women tied the belt on the left side, and the man on the right. The belts were decorated with geometric patterns - in addition to decoration, this served as a talisman.

Hats

Russian headdresses varied in shape. The main material was fur (usually sheepskin), wool in the form of felt and cloth, and less often other fabrics; they were shaped like a cone, cylinder or hemisphere. Felted hats were called hats, or horse hats. Semicircular headdresses also include the triukh - a fur hat with earmuffs. Later, caps with visors on the band became widespread.

Women's headdresses were more varied, but all their diversity comes down to several types: a scarf, a hat, a cap and a maiden's crown. Religious beliefs required a married woman to carefully hide her hair from prying eyes. It was considered a great sin and disgrace to “expose” even a strand of hair. “They punished with general contempt those who “fouled” a woman or tried to do so; Northern Russian residents used to even have trials of those who “cossified” a woman by tearing off her cap from her head.”

Married women wore their hair around their heads, and their headdress was a kokoshnik, which was decorated with gold embroidery, pearls or beads. At the same time as kokoshniks, there were also warriors, shamshurs, collections - all these are varieties of caps. The warriors sewed from thin fabric in the form of caps with a chintz lining, and shamshurs had a quilted top on a canvas base. The back of the warrior was decorated with lush floral patterns. Married women always wore a scarf or shawl over small headdresses that hid their hair.

The headscarf worn by Russian women is the result of the development of the oriental veil. The manner of tying a scarf under the chin came to Rus' in the 16th-17th centuries, and they learned it from the Germans.

Animal skins, tanned leather, less often fur, tree bark, and hemp rope were used as materials for making shoes. The oldest among Russians should be considered leather shoes, which were not sewn, but wrinkled - they tied a piece of leather with ropes so that folds formed on the sides and tied it to the foot with a long rope. Such shoes are considered a direct continuation of ancient shoes, when the skin of a small animal was tied to the foot. These shoes were called pistons.

Leather shoes similar to pistons, but not wrinkled, but sewn, with a hemmed sole, are called cats; they were worn by both women and men both on weekdays and on holidays. Their name comes from the word “roll”, since they were originally rolled from wool.

The Russians first sewed leather shoes with high tops - boots (chebots) - without heels, which were replaced by a small iron shoe on the heel; they also wore shoe covers - the sole was sewn to them from the inside, they were wide and awkward.

All the types of shoes described above were worn by both men and women. Special women's shoes include shoes - slippers - with a low top.

The most common shoes can be considered bast shoes, which are known everywhere in the region. These are shoes woven from tree bast, like sandals, which were tied to the foot with long cords (supports); for warmth, an edge was sewn or tied to the bast shoes - a strip of canvas fabric. In rainy weather, a small plank was tied to the bast shoes - the sole. With bast shoes and other low shoes they wore onuchi - long narrow strips of fabric made of wool or hemp. This fabric was wrapped around the foot and shin up to the knee, and on top of it they wrapped the leg crosswise with long laces - extinguishers. Onuchi was made from white canvas of average quality. Bast was prepared in the summer and stored in reels, and on long winter evenings the head of the family wove bast shoes for the whole family, using a tool called kochedyk. On average, one pair of bast shoes wore out in three to four days.

Felted shoes appeared among the Russians at the end of the 17th - beginning of the 18th centuries. Wool was used to roll boots, felt boots, and chuni; leather soles were often sewn onto these shoes for strength.

Baby suit

The very first diaper for a newborn was most often the shirt of the father (boy) or mother (girl). Subsequently, they tried to cut children's clothes not from newly woven fabric, but from the old clothes of their parents. They did this not out of stinginess, not out of poverty, and not even because the soft, washed material does not irritate the baby’s delicate skin. The whole secret, according to the beliefs of our ancestors, is in the sacred power, or, in today’s terms, in the biofield of the parents, which can protect their child from damage and the evil eye.

Children's clothing of the ancient Slavs was the same for girls and boys and consisted of one long, toe-length, linen shirt. Children received the right to “adult” clothes only after initiation rites.

This tradition lasted for an exceptionally long time in the Slavic environment, especially in the villages, which were little exposed to fashion trends. Over the centuries, the ancient ritual of transition from the category of “children” to the category of “youth” was lost; many of its elements became part of the wedding ceremony. So, back in the 19th century, in some regions of Russia, fully grown boys and girls sometimes wore children’s clothing before their wedding - a shirt held with a belt. In a number of other places, the child’s clothing was an ordinary peasant costume, only in miniature. Loving mothers always tried to decorate children's clothes - the collars, sleeves and hem of the shirt were covered with abundant embroidery. This is understandable, since in ancient times it had a protective meaning. “A girl under 15 years old, and more often before marriage, wore a belted shirt, and on holidays they put an apron with sleeves on top - shushpan.”

Girls put on a sundress only after getting married; there was a whole ritual of unbraiding their hair and changing into a sundress.

A girl's headdress differed from a woman's one in that girls did not need to cover their hair, they did not hide their braids; uncovered hair was considered an indicator of the girl’s “purity.” Girls wore a bandage, a crown or a headband, poor girls wore a bandage made of motley hair, and richer girls wore a silk bandage decorated with embroidery or beads. Bandages and ribbons only framed the head, and only wedding headdresses - crowns - completely covered the head.

CONTENT

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….2

Chapter 1. Main features of Russian folk costume………………………3

1.1.Types of clothing and cut features…………………………………………….3

1.2.Color - language of the people and decorations, decoration.................................... .............…4

Chapter 2. Main stages of development of modeling 1930-1990…………..6

Chapter 3. Functionality of clothing and folk traditions………………………10

Chapter 4. Traditions and modernity……………………………………………..13

Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….14

Used literature………………………………………………………15

Introduction.

Folk costume is a priceless and integral heritage of the culture of the people, accumulated over centuries. Clothing, which has come a long way in its development, is closely connected with the history and aesthetic views of its creators. The art of modern costume cannot develop in isolation from folk, national traditions. Without a deep study of traditions, the progressive development of any type and genre of modern art is impossible.

Folk costume is not only a bright, original element of culture, but also a synthesis of various types of decorative creativity, which until the mid-twentieth century brought traditional elements of cut, ornament, use of materials and decorations characteristic of Russian clothing in the past.

The formation of the composition, cut, and ornamentation features of the Russian costume was influenced by the geographical environment and climatic conditions, the economic structure and the level of development of the productive forces. Important factors were historical and social processes that contributed to the creation of special forms of clothing, and the role of local cultural traditions was significant.

Until the 1930s, folk costume was an integral part of the artistic appearance of the rural population: Russian round dances, wedding ceremonies, gatherings, etc. Many nations still retain their national costume as a festive costume. It is being mastered as an artistic heritage by modern fashion designers and lives in the creativity of folk song and dance ensembles.

Chapter 1. Main features of Russian folk costume

1.1.Types of clothing and cut features

Traditionally, peasant clothing, not affected by official legislation, has retained stable forms worked out over centuries that determine its originality. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, the peasant costume concentrated the most typical features of the Old Russian costume: cut, decorative techniques, method of wearing and much more.

The Russian suit is characterized by a straight cut with freely falling lines. It is worth emphasizing the traditional nature of folk costume, which is expressed in a number of principles and qualities. Folk costume is characterized by a rational design, determined by the width of homespun fabrics, the structure of the human figure, and the purpose of things in everyday life.

The main parts of the clothing were cut by folding the panels in half along the weft or warp. For wedges, if necessary, the panels were folded diagonally. The garment parts, sewn along straight lines, were supplemented with rectangular or oblique inserts (poles, gussets) for freedom of movement. There is a certain archaism in this specific cut. Typical features also include the significant length of clothing, especially the long sleeves of women's shirts, the arrangement of decor, the multi-layered ensemble consisting of several clothes worn one on top of the other, rich coloring with a contrasting combination of colors of individual parts of the costume.

Women's outer seasonal clothing, with the exception of decoration and some details, was basically little different from men's. It was most often sewn from undyed, natural-colored cloth. In different regions it received different names: caftan, armyak, retinue, zipun. Clothes with a robe-like cut, with a large collar, were typical; a cut with an undercut and pleats on the back was widespread. Outerwear could have pockets in the side seams or folds.

Women wore seasonal clothes with scarves. In winter, sheepskin coats, sheepskin coats and sheepskin coats of black or brown-brown color were used as clothing. They were worn, as a rule, with the fur inside and were naked or covered with dye. The decoration of fur coats is similar to that of caftans; sometimes fur coats were trimmed with fur of a different color. In addition, in the north, in the Lower Volga region, the Urals and Siberia, there were clothes made from animal skins such as sable, and they were even worn on the road over a sheepskin coat, fur coat, caftan, as well as massive long robe-like clothes made of cloth with a large semi-covered collar. When leaving the house, all outer clothing was raised with long belts and sashes.

Any peasant costume was necessarily complemented by wicker or rolled shoes. Just like outerwear, shoes were almost the same for women and men and differed only in size and decoration.

Headdresses play a special role in deciding the composition of the costume. Women's headdress also retains archaic features in its forms and decor.

1.2 .Color is the language of the people and decoration, decoration.

Color is a special way of expressing human feelings. The leading color tones in folk clothing are white, red and blue. Red was the most favorite color among the people. The words “red sun”, “spring is red”, “red maiden” and others expressed ideas about the highest beauty. Clothes made of red fabric (sarafans, ponevs) and embroidery with red thread were considered the most elegant. The different shades and intensities of red create a very subtle harmony. Black color was used, as a rule, to enrich and enhance the sound of the main tones, but in some cases it is the leading color.

Decorative clothing of a folk costume may include other bright colors, often contrasting, such as green, blue, orange, yellow. The general color scheme of folk clothing depends on the proportions of parts of different color tones, the nature of the embroidery, the ratio of the areas of the ornamentation and the background.

Decorations and finishing.

Clothes were decorated in three ways: quality, embroidery, sewing on various materials - lace, braid, and the like. The pattern was formed by a weft thread that overlapped the warp threads. Elements of the ornament alternated with gaps in the background. The woven pattern was used mainly for making sleeves, the bottom of shirts, and aprons. Often patterned stripes were skillfully complemented by embroidery, creating a decor of exceptional beauty. Embroidery of folk clothing is distinguished by a wide variety of techniques and methods. For embroidery, special threads with a special twist were used. They were made from linen and wool fibers and dyed with natural dyes.

In most cases, several types of embroidery techniques were used to use the pattern. With all the variety of embroidery techniques, folk embroidery on clothing is distinguished by its extraordinary consistency of artistic design and technical execution. As a rule, in the ornamentation of clothing, all methods of decoration were combined: patterns made by embroidery and weaving were complemented by stripes made of ribbons, braid, and braid. They all harmonized with each other.

So, the most general features characteristic of the costume of the period of the 7th-19th centuries include the following:

a) static, straight, widened downward silhouette of the product and sleeves, massiveness, as a rule, increasing downwards, is emphasized by shoes - woven bast shoes with thick onuches, large gathered boots and heavy sweats - shoes, which were sometimes worn on seven to eight pairs of thick woolen shoes stocking;

b) the predominance of symmetrical compositions with the rhythm of rounded lines in details, decoration, and additions;

c) the use of homespun, and later factory fabric, finishing with embroidery, lace, sewing, fur, fabric of a different color; creating a dynamic shape of the suit through the use of contrasting colors;

d) the great importance of the headdress in deciding the composition of the costume.

All these features are of great importance for the fashion designer as principles that must be followed in creativity. You should pay attention to the properties of a folk costume, such as the shape and cut of the costume, silhouette lines, design lines, which are of interest from the point of view of not only rationality, but also beauty. This is also the decoration of folk clothing, color, pattern technique, sense of material, etc. It is these features of folk costume that constitute the content of the concept “folk motifs”. Folk motifs are the refraction of folk traditions in the modern art of creating things.

Chapter 2. Main stages of development of modeling 1930-1990.

Folk costume, its design, decor, color combinations were used in modeling of the 20th century. How was the connection between folk costume and clothing modeling carried out, in what forms did it manifest itself, how did the artists work? Samples of modern costume are not kept in museums, like ceramics, for example. Information about modeling of past times can only be found on the pages of various fashion magazines.

The 1930s were a time of flourishing of national cultures, a time of developing interest in folk decorative art. Instead of modeling laboratories, the Moscow House of Models, uniting the best fashion designers, is becoming the head of fashion. During these years, its study began in relation to creative work on costumes. This was observed not only in the activities of the Moscow House of Models, but also in the costume of the population. To a large extent, this fact was determined by the need to make clothes from smoothly dyed fabrics. Their monotonous surface had to be decorated with embroidery and finishing fabrics. At that time, straight-cut linen dresses with a large neckline and sleeveless were common. Dresses of this style were decorated with embroidery and generally gave great scope in the use of the basics of folk costume.

Publications in the Traditions section

They meet you by their clothes

Russian women, even simple peasant women, were rare fashionistas. Their voluminous chests contained many - at least three dozen - very different outfits. Our ancestors especially loved headdresses - simple, for every day, and festive ones, embroidered with beads, decorated with gems. And how they loved beads!.. The formation of any national costume (be it English, Chinese or the Bora Bora tribe), its cut and ornamentation was always influenced by factors such as geographical location, climate, and the main occupations of the people.

“The more closely you study Russian folk costume as a work of art, the more values you find in it, and it becomes a figurative chronicle of the life of our ancestors, which, through the language of color, shape, and ornament, reveals to us many of the hidden secrets and laws of beauty of folk art.”

M.N. Mertsalova. "The Poetry of Folk Costume"

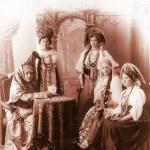

In Russian costumes. Murom, 1906–1907. Private collection (Kazankov archive)

So in the Russian costume, which began to take shape by the 12th century, there is detailed information about our people - a worker, a plowman, a farmer, living for centuries in conditions of short summers and long, fierce winters. What to do on endless winter evenings, when a blizzard howls outside the window and a blizzard blows? Our handicraft ancestors wove, sewed, and embroidered. They created. “There is the beauty of movement and the beauty of peace. Russian folk costume is the beauty of peace", wrote the artist Ivan Bilibin.

Shirt

The main element of Russian costume. Composite or one-piece, made of cotton, linen, silk, muslin or simple canvas, the shirt certainly reached the ankles. The hem, sleeves and collars of shirts, and sometimes the chest part, were decorated with embroidery, braid, and patterns. Moreover, colors and ornaments differed depending on the region and province. Voronezh women preferred black embroidery, strict and sophisticated. In the Tula and Kursk regions, shirts, as a rule, are tightly embroidered with red threads. In the northern and central provinces, red, blue and black, sometimes gold, predominated.

Different shirts were worn depending on what work had to be done. There were “mowing” and “stubble” shirts, and there was also a “fishing” shirt. It is interesting that the work shirt for the harvest was always richly decorated and equated to a festive one.

Russian women often embroidered spell signs or prayer amulet on their shirts, because they believed that by using the fruits of the earth for food, taking life from wheat, rye or fish, they violate natural harmony and come into conflict with nature. Before killing an animal or mowing the grass, the woman said: “Forgive me, Lord!”

Fishing shirt. End of the 19th century. Arkhangelsk province, Pinezhsky district, Nikitinskaya volost, Shardonemskoye village.

Mowing shirt. Vologda province. II half of the 19th century

By the way, about the etymology of the word “shirt”. It comes not at all from the verb “to chop” (although chopping wood in such clothes is certainly convenient), but from the Old Russian word “chopping” - boundary, edge. Therefore, the shirt is a sewn cloth with scars. Previously they used to say not “hem”, but “hem”. However, this expression is still found today.

Sundress

The word “sarafan” comes from the Persian “saran pa” - “over the head”. It was first mentioned in the Nikon Chronicle of 1376. As a rule, a trapezoidal silhouette, a sundress was worn over a shirt. At first it was purely men's attire, the ceremonial vestment of princes with long folding sleeves, sewn from expensive fabrics - silk, velvet, brocade. From nobles, the sundress passed to the clergy and only then became established in the women's wardrobe.

Sundresses were of several types: blind, swing, straight. Swing ones were sewn from two panels, which were connected using beautiful buttons or fasteners. A straight (round) sundress was fastened with straps. A blind oblique sundress with longitudinal wedges and beveled inserts on the sides was also popular.

Sundresses with soul warmers

Recreated holiday sundresses

The most common colors and shades for sundresses are dark blue, green, red, light blue, and dark cherry. Festive and wedding sundresses were made mainly from brocade or silk, and everyday sundresses were made from coarse cloth or chintz. However, the overseas word “sarafan” was rarely heard in Russian villages. More often - a kostych, damask, kumachnik, bruise or kosoklinnik.

“Beauties of different classes dressed up almost identically - the only difference was the price of furs, the weight of gold and the shine of stones. When going out, a commoner would put on a long shirt, over it an embroidered sundress and a jacket trimmed with fur or brocade. The noblewoman - a shirt, an outer dress, a letnik (a garment that flares out at the bottom with precious buttons), and on top there is also a fur coat for added importance.”

Veronica Batkhan. "Russian beauties"

A short warm-up jacket (something like a modern jacket) was worn over the sundress, which was festive clothing for the peasants, and everyday clothing for the nobility. The shower jacket (katsaveika, padded jacket) was made from expensive, dense fabrics - velvet, brocade.

Portrait of Catherine II in Russian dress. Painting by Stefano Torelli

Portrait of Catherine II in shugai and kokoshnik. Painting by Vigilius Eriksen

Portrait of Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna in Russian costume." Unknown artist. 1790javascript:void(0)

Empress Catherine the Great, who was reputed to be a trendsetter, brought back into use the Russian sarafan, clothing that had been largely forgotten by the Russian upper class after the reforms of Peter, who not only shaved the beards of the boyars, but also forbade wearing traditional clothes, forcing his subjects to follow the European style. The Empress considered it necessary to instill in Russian subjects a sense of national dignity and pride, a sense of historical self-sufficiency. As soon as she sat on the Russian throne, Catherine began to dress in Russian dress, setting an example for the ladies of the court. Once, at a reception with Emperor Joseph II, Ekaterina Alekseevna appeared in a scarlet velvet Russian dress, studded with large pearls, with a star on her chest and a diamond diadem on her head. And here is another documentary evidence: “The Empress was in Russian attire - a light green silk dress with a short train and a bodice of gold brocade, with long sleeves,”- wrote an Englishman who visited the Russian court.

Poneva

Just a skirt. An essential part of a married woman's wardrobe. Poneva consisted of three panels and could be blind or hinged. As a rule, its length depended on the length of the woman's shirt. The hem of the poneva was decorated with patterns and embroidery. Most often, poneva was made from wool-blend fabric in a checkered pattern.

It was worn on a shirt and wrapped around the hips, and was held at the waist by a woolen cord (gashnik). An apron was often worn in front. In Rus', for girls who had reached adulthood, there was a ritual of putting on a poneva, which indicated that the girl could already be betrothed.

Belt

Women's wool belts

Belts with Slavic patterns

Machine for weaving belts

An integral part of not only the Russian costume, the custom of wearing a belt is widespread among many peoples of the world. In Rus', it has long been customary for a woman’s undershirt to always be belted; there was even a ritual of girding a newborn girl. The belt - a magic circle - protected against evil spirits, and therefore it was not removed even in the bathhouse. Walking without a belt was considered a great sin. Hence the meaning of the word “unbelt” - to become insolent, to forget about decency. By the end of the 19th century, in some southern regions it became acceptable to wear a belt simply under a sundress. The belts were made of wool, linen and cotton, and they were crocheted or woven. Sometimes the sash could reach a length of three meters; these were worn by unmarried girls; hem with a voluminous geometric pattern - married women. A yellow-red belt made of woolen fabric, decorated with braid and ribbons, was worn on holidays.

Apron

Women's urban costume in folk style: jacket, apron. Russia, late 19th century

Women's costume from the Moscow province. Restoration, contemporary photography

It not only protected clothes from contamination, but also served as an additional decoration for a festive outfit, giving it a finished and monumental look. The apron was worn over a shirt, sundress and poneva. However, in Rus' the word “zapon” was more in use - from the verb “zapinati” (to close, to detain). The defining and most lavishly decorated part of the outfit is with patterns, silk ribbons and finishing inserts. The edge is decorated with lace and frills. From the embroidery on the apron it was possible, like from a book, to read the history of a woman’s life: the creation of a family, the number and gender of children, deceased relatives and the preferences of the owner. Every curl, every stitch emphasized individuality.

Headdress

The headdress depended on age and marital status. He predetermined the entire composition of the costume. Girls' headdresses left part of their hair open and were quite simple: ribbons, headbands, hoops, openwork crowns, and folded scarves.

After the wedding and the ceremony of “unbraiding the braid,” the girl acquired the status of a woman and wore a “kitka of a young woman.” With the birth of the first child, it was replaced by a horned kichka or a high spade-shaped headdress, a symbol of fertility and the ability to bear children. Married women were required to cover their hair completely under a head covering. According to ancient Russian custom, a scarf (ubrus) was worn over the kichka.

Kokoshnik was the ceremonial headdress of a married woman. Married women wore a kichka and kokoshnik when they left the house, and at home they usually wore a povoinik (cap) and a scarf.

The age of the owners was easily determined by the color scheme. Young girls dressed most colorfully before the birth of a child. The costumes of the elderly and children were distinguished by a modest palette.

The women's costume was replete with patterns. The embroidery on sundresses and shirts echoed the carved frame of a village hut. Images of people, animals, birds, plants and geometric shapes were woven into the ornament. Sun signs, circles, crosses, rhombic figures, deer, and birds predominated.

Cabbage style

A distinctive feature of the Russian national costume is its multi-layered nature. The everyday suit was as simple as possible; it consisted of the most necessary elements. For comparison: a married woman’s festive costume could include about 20 items, while an everyday costume could include only seven. The girls wore the three-piece ensemble to every appearance. The shirt was complemented with a sundress and kokoshnik or a poneva and a magpie. According to legends, multi-layered, loose clothing protected the hostess from the evil eye. Wearing less than three layers of dresses was considered indecent. The multi-layered robes of the nobility emphasized their wealth.

The main fabrics used for folk peasant clothing were homespun canvas and wool, and from the middle of the 19th century - factory-made silk, satin, brocade with ornaments, calico, chintz, and satin. A trapezoidal or straight monumental silhouette, the main types of cut, picturesque decorative and color schemes, kitties, magpies - all this existed in the peasant environment until the middle - late 19th century, when urban fashion began to supplant traditional costume. Clothes are increasingly purchased in stores, and less often sewn to order.

We thank the artists Tatyana, Margarita and Tais Karelin - laureates of international and city national costume competitions and teachers - for providing photographs.

Look how we are dressed?! Look who we look like?! Anyone, but not the Russians. To be Russian is not only to think in Russian, but also to look like a Russian person. So, let's change our wardrobe. The following items of clothing should be included:

This is the cornerstone of the Russian wardrobe. Almost all other types of men's outerwear in Rus' were versions of the kaftan. In the 10th century, it was introduced into Russian fashion by the Varangians, who, in turn, picked it up from the Persians. At first, only princes and boyars wore it, but over time, the caftan penetrated into the “toilets” of all other classes: from priests to peasants. For the nobility, caftans were made from light silk fabrics, brocade or satin, and the edges were often trimmed with fur. Near the edge, gold or silver lace was sewn along the flaps, cuffs, and hem. The caftan was extremely comfortable clothing and hid the flaws of its owner's figure. He gave significance to plain-looking people, solidity to thin people, grandeur to fat people.

Where to wear it?

For business meetings. A good caftan can easily replace a dull suit and tie.

This type of caftan was wide at the hem, up to three meters, with long sleeves hanging down to the ground. Thanks to the fairies, the saying “work carelessly” was born. It was worn both in cold winter and hot summer. Summer furs were thinly lined, and winter ones were lined with fur. This item of clothing was sewn from different fabrics - from brocade and velvet (wealthy people) to homespun and cotton fabrics (peasants). Rich people wore feryaz on other caftans, and poor people - directly on shirts. The budget version of the feryazi was tied with cords, and its buttonholes were modest and did not exceed 3-5 in number. Exclusive caftans were decorated with seven expensive buttonholes with tassels, which could be either tied or fastened. The edges of the ferjazi were trimmed with galloon or gold lace.

Where to wear it?

For major celebrations and official receptions held outdoors.

It is somewhat reminiscent of a feryaz, but the opashen is less solemn. As a rule, it served as a duster or summer coat. The opashen was made of cloth or wool without lining, without decorations, sometimes even without fasteners. Hem-length sleeves were sewn in only at the back. The entire front part of the armhole and cuff of the sleeve was treated with facings or braid, thanks to which the opashen could be worn as a sleeveless vest: the arms in the sleeves from the lower caftan were inserted into the slits, and the sleeves of the opashen were left hanging at the sides or tied back. In cold weather, they were worn on the arms, and part of the sleeve could hang, protecting the hand and fingers from the cold.

Where to wear it?

Can easily replace a casual coat or raincoat.

A “casual” version of the caftan with a fitted short silhouette and fur trim. It was sewn on fur or cotton wool with a fur or velvet collar. Russian boyars spied this caftan during the defense of Polotsk in 1579 from the Hungarian infantry soldiers who fought on the side of the Poles. Actually, the name of the caftan itself comes from the name of their Hungarian commander Kaspar Bekes. The Russian army lost Polotsk, but brought prisoners and “fashionable” Hungarians to Moscow. Measurements were taken from the “tongue” caftans, and another piece of clothing appeared in the Russian wardrobe.

Where to wear it?

“Bekesha” can become casual, semi-sportswear, and replace, for example, a jacket or down jacket.

A lightweight, minimalist version of the caftan made from homespun cloth. The zipun does not have any decorations or frills in the form of a stand-up collar. But it is very functional: it does not restrict movement. Zipuns were worn mainly by peasants and Cossacks. The latter even called their Cossack trade - going for zipuns. And highway robbers were called “zipunniks.”

Where to wear it?

Perfect for garden work in cool weather. Also not suitable for fishing and hunting.

Epancha was created for bad weather. It was a sleeveless cloak with a wide turn-down collar. They sewed epancha from cloth or felt and soaked it in drying oil. As a rule, these clothes were decorated with stripes in five places of two nests. Stripes - transverse stripes according to the number of buttons. Each patch had a buttonhole, so later the patches came to be called buttonholes. Epancha was so popular in Rus' that it can even be seen on the coat of arms of Ryazan.

Where to wear it?

An excellent replacement for a parka and a mackintosh (a raincoat, not the one from Apple).

Headdress.

It is impossible to imagine a Russian person of the 17th century appearing on the street without a headdress. This was a monstrous violation of decency. In pre-Petrine times, the central “head” attribute was a cap: a pointed or spherical shape with a slightly lagging band - a rim that fits the head. Noble people wore caps made of velvet, brocade or silk and upholstered in valuable fur. The common people were content with felt or felted hats, which were called “felt boots.” In hot weather or at home, Russians wore so-called “tafya”, caps that covered the tops of their heads, reminiscent of skullcaps. Noble citizens had tafyas embroidered with silk or gold threads and decorated with precious stones.

Where to wear it?

The cap will easily replace the ridiculous-looking knitted hats accepted today. And tafya will supplant “alien” baseball caps and other “Panama hats” in the summer.

Read about another extremely important accessory of the Russian wardrobe.